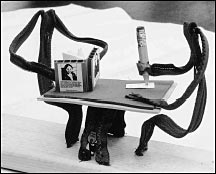

In this sculpture she created with a group, she is depicted as the zipper in the lower left. The teacher (middle zipper) and group are zippers of the same colour. She used a contrasting zipper colour along with beads and a feather to represent her First Nations heritage. Diane’s story about the sculpture: When I was in school, the teacher always faced away from me, and I was always saying “I want some help, I need some help.” The teacher pays attention to all those other same colour people, who are like angels and can do no w rong and th ey are all connected. This is a story of discrimination, but it can be the same for anyone who feels left out, who feels on the edge. The experience of creating sculptures together contributed to my deeper awareness about students’ experiences at the Centre and pushed me to uncover and reflect upon my own assumptions. Issues and stories emerged while talking about the sculptures that never came up during our conversations and interviews. Tool of ReciprocityI see research as a process of building relationships and learning together from those relationships. Thus one of my research issues was a concern about reciprocity – I wanted to publicly acknowledge the time and energy people gave through interviews and the many conversations. I wanted to honour the relationships we formed through the process of the research. I had noticed that when people from the Centre went out in public for fundraising or public relations work, they used paper signs to tell where they were from. I decided to make them a portable, re-usable sign, and created a cloth banner using zipper letters to spell out Reading & Writing Centre. I see research as a process of building relationships and learning together from those relationships. I also wanted to celebrate their work as readers and writers. The Reading and Writing Centre regularly informally publishes student writing. They have also formally published two books by students. In Reader / Writer one of the zippers is reading a miniature version of one of those books. After I gave them this sculpture, they published the second book, so for that book launch I created a tiny replica of that book as well. Tensions & LimitationsAlthough my original intent in using artifacts was to minimize the use of written text with student participants, I was not initially cognizant that the use of art is another kind of literacy, where we are required to ‘read’ the artifact. Rick, one of the students, helped me attune to the necessity of assuming the role of guide when viewing the artifacts. During our Group Talk, when people had been laughing about the variety of ways to change the positions of the sculptural figures, I noticed that Rick was relatively quiet. He commented to me later that he could understand the humour only after I had explained that the zippers were human teacher / student characters in the Hovering sculpture. We also further talked about the differences in people’s responses to the artifacts and how interpretation can vary from person to person. One student’s interpretation of the zippers caused me to reflect upon these materials as gender specific, perhaps seen as women’s sewing notions. During the beginning of our first group talk, I had placed several zippers (with the wire sewn into them) and some foam bases around the tables where we would be sitting. Daniel picked up one of the zippers, played around with it, bending it into shapes. Then he attempted to engage the two other male students, Rick and Matthew, in a bantering and comparison of the size and stiffness of their zippers, asking them, “How big is your zipper?” and laughing. They didn’t respond, and after a few more comments to them, Daniel threw his zipper on the table, sayin,g “this is so stupid.” He turned his swivel chair away from the table. Daniel’s machismo engagement with the zippers was a reading and interp retation that wasn’t shared by others at the time. I chose not to comment or respond as well. I created sculptural artifacts that represented my responses to observations and interviews with students, and then shared those artifacts with people at the centre. Throughout the research process, I wanted to respond respectfully within all encounters with participants, and remained conscious of not assuming roles of art connoisseur or the rapist. The use of artifacts can open up potentially powerful emotional places, thus it is important to tread carefully and attentively. During that same group talk, Bert and Matthew chose to play around with the zippers. One of them set three zippers into a foam base, explaining that two zippers are “yakking together” and the third one is more distant and backing away. Matthew immediately responded to Bert’s creation, saying that he related to the third zipper character that was backing away because he feels a bit like an outsider at the Centre. While we discussed those feelings, Matthew and Bert changed and manipulated the sculpture to show how Matthew would like to see himself at the Centre – he faced the zipper towards and closer to the other two talking together. Another interesting ‘reading’ of the artifacts occurred by the general public. After the Adult Student workshop, we placed several of the creations in one of the storefront display windows and later heard that passers-by thought the Centre might be a new sewing notions store! Final WordsMy use of artifacts in research has been a provocative exploration that continues. The use of art and imagination as tools can be integrated into the general research process to help open up and go to places not always accessible through research traditions of talking, listening and observing. Research is a place where we work to uncover unacknowledged assumptions and implicit knowledge. The ethnographer’s job is to dig deeper into what is assumed to be common sense or normal behaviour. “To tap into imagination is to become able to break with what is supposedly fixed and finished, objectively and independently real. It is to see beyond what the imaginer has called normal or “common-sensible” and to carve out new orders in experience. Doing so, a person may become freed to glimpse what might be, to form notions of what should be and what is not yet. And the same pe rson may, at the same time, remain in to u ch with what presumably is.” (Greene p. 19)

Bonnie Soroke is presently completing her thesis research, mothering a teen-aged son, facilitating art workshops and doing consulting work with the RiPAL network. She has also worked as an early childhood educator, ESL tutor, EFL teacher in Japan, tree planter and VOJ (various other jobs). Music, art and motorcycling feed her soul.

|