Between a rock and a hard place with literacy rate statisticsby Susan Sussman Damned if we don'tWhere dozens of social and economic issues compete every day for media attention, public awareness, political support and a bigger share of public funding, nearly every social, political and economic argument is backed up by statistical research. In the month of August 2003 alone, statistical data supported reports in the Toronto Star and Globe and Mail on baby boomers’ retirement worries, childhood obesity, crime rates, drug trafficking, the economic integration of immigrants in Canada, the effects of family income on university attendance, gender differences in performance on standardized reading tests, homelessness, home- schooling, infant mortality, major depression and other mental illnesses among Canadians, and seniors requiring home care services. Most advocates find it impossible

to move literacy issue Journalists, decision makers and corporate leaders with statistics that point to staggering numbers of Canadians with literacy difficulties. Most advocates find it impossible to move literacy issues into the spotlight and onto the public policy agenda without referring to literacy rate statistics. And the influence of literacy rate statistics doesn’t end there; it is seen throughout the policy development process. Once decision makers have bought into the notion that literacy warrants a public policy response, the issue literacy has to be framed further. What is the specific problem in need of attention? Who suffers from it and how? Who gains from it? What causes it? Population literacy surveys, statistics that derive from them, and interpretations of that data all influence the way literacy is framed as a policy issue. For example, reports on the International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS), issued by the OECD and Statistics Canada, frame literacy as a human capital issue, crucial to the economic performance of industrialized nations in an increasingly competitive global economy. Forecasting is used in policy development to help decision makers make better decisions. Where literacy is regarded as a public policy concern, literacy rate data is bound to show up in the forecasts. For example, consider the following notes from a presentation on the federal government’s Skills and Learning Agenda (1999).

Goal-setting and decision-making about the allocation of public resources are also essential for policy development. These usually involve a priority-setting process in which problems, goals, services, geographic areas and/or specific population groups are ranked. Data from IALS has been used to make the case for placing adult literacy at the top of the priority lists of industrialized nations, primarily as a labour force development issue. Most Canadian literacy advocates acknowledge that reports from IALS have been instrumental in preserving or increasing funding for literacy. Once policy goals are determined, options for valuated and selected. Some argue that literacy assessment data from large-scale surveys must be used to inform decisions about how best to address literacy problems.

Finally, policy outcomes are reviewed and ev development process are commonly the benchmark against which outcomes are measured. When expectations have been expressed in terms of changes in literacy rates, this data becomes a yardstick used to evaluate policy outcomes. For example, the 2001 Throne Speech included the goal of “significantly increasing the proportion of adults with higher-level skills.” In a nutshell, the issue of adult literacy likely never would have gained the public and political recognition it enjoys in Canada today were it not for the startling statistical results of national literacy surveys like IALS. To a considerable extent, the design of current policies and programs has been influenced by interpretation of literacy rate data. "Statistics are human beings with the tears wiped off."

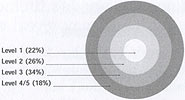

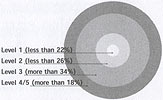

Damned if we doFew people, including those Canadians involved in adult literacy work, have ever formally studied the sciences of statistics or research design. Thus few can confidently examine statistical research findings and interpret them independently. People working in the literacy field who do have a research background rarely have the time or mandate to critically consider new research. As far as many people are concerned, statistics are alien and alienating. Meanwhile, most research experts agree that all existing methods of estimating literacy rates have significant conceptual and technical limitations. For starters, there’s no broad consensus about what it means to be literate. This is a big problem. Logic dictates that a shared understanding of the word literacy is a prerequisite for a shared understanding of how to measure it. Even those who define literacy in the same way may disagree about if and/or how it should be measured. Words used in a definition are one thing; the phenomenon captured by a particular assessment method is another. Many researchers question the validity of all assessment methods used so far, arguing that they fail to reflect how real people use literacy skills in their real lives. The science of statistics complicates the problem further when the results of thousands of individual literacy assessments are aggregated into population literacy rate estimates. Population statistics tend to diminish the complex realities of individuals in service of creating mathematical findings. This problem led one pundit to say, “Statistics are human beings with the tears wiped off.” Different experts can legitimate ly draw different conclusions from the same data. A skilled mathematician who tortures numbers long enough can make them confess to almost any thing. The pliable nature of statistics led Mark Twain to say, “There are three kinds of lies – lies, damned lies and statistics.” Many of our colleagues are wary of statistics believing that numbers can and will be manipulated to prove whatever a researcher wants them to show. Numbers that quantify Canada’s literacy challenges may engage us, but they may also enrage us. They may reveal a lot, but they may conceal as much. Thus literacy advocates and policy makers are damned if we do and damned if we don’t use literacy statistics to help us do our jobs. Without them we seem unable to gain and keep public and political support for broad-based strategies to improve literacy levels. While the statistics can help put the issue on the map, they don’t always lead us in the right direction. Thus numbers that quantify Canada’s literacy challenges may engage us, but they may also enrage us. They may reveal a lot, but they may conceal as much. While discourse on literacy is influenced by the numbers at the policy level, literacy rate estimates don’t necessarily reflect literacy problems as learners and practitioners in programs understand them. We need to understand statistics, and when, how and why they are used. Tensions between the opportunities and challenges associated with using literacy statistics generate noise and confusion in Canada’s system of literacy initiatives. What get said about literacy in public awareness campaigns (e.g. “22 per cent of adult Canadians have serious difficulty dealing with print”) may be highly relevant to literacy rate statistics but not entirely relevant to what goes on in literacy programs, which tend to be shaped more by realities and needs of individual learners and practitioners. Many of the important gains made in literacy programs may never show up in literacy rate statistics. Thus we run the risk of winning public and political support today because of what the numbers show, only to loose it tomorrow because of what the numbers won’t show. What to do?For better or worse, literacy rate statistics will continue to be used wherever literacy policy decisions Canada’s literacy policies cannot simply ignore the tead, we need to understand them and when, how and why they are used. We don’t necessarily need to become statisticians but we do need to know what questions to ask about large scale literacy assessment research, and we need to develop the will and the ability to become critical consumers of literacy rate statistics. Towards these ends, I offer four recommendations.

Susan Sussman has worked in literacy since 1993, in the position of Executive Director of the Ontario Literacy Coalition, as the President and board member of the Movement for Canadian Literacy, and as an independent researcher. Sussman holds a master’s degree from Columbia University's Teachers College and a bachelor's degree from the City University of New York.

|